Medical Marijuana Laws and Cannabis UseIntersections of Health and Policy

For psychiatrists, understanding the effect of marijuana laws is essential because of the potential effect of cannabis on mental health.5 To start with, individuals with mental illness are more likely to use marijuana, and both acute intoxication and chronic use can exacerbate psychiatric symptoms. Also, early cannabis use has been associated with onset of psychosis and risk for suicidality, and cannabis use can interfere with the treatment of mental disorders. Understanding the potential effect of cannabis use on mental illness is advanced by careful population studies, such as the work by Hasin et al,4 as well as fast advances in neuroscience.6

Since the discovery in the early 1990s of the cannabinoid-1 and cannabinoid-2 receptors along with their endogenous agonists (ie, endocannabinoids), the knowledge of the role of the endogenous endocannabinoid system in the development and function of the human brain has expanded. Cannabinoid-1 receptors have their highest concentration in the cortex, basal ganglia, hippocampus, and cerebellum, areas involved in decision making and self-regulation, reward and motivation, memory and conditioning, and time perception and motor coordination, respectively.5,6 In the brain, cannabinoid-2 receptors are primarily concentrated in immune cells (microglia), although recent evidence indicates that they are also expressed at low levels in some neuronal populations. Endocannabinoids are primarily synthesized postsynaptically in response to stimulation, acting as retrograde messengers to suppress excitatory and inhibitory presynaptic neurons.6 Thus, endocannabinoid signaling acts as part of a feedback loop, playing a crucial role in fine-tuning neuronal activity across a wide range of circuits. Understanding these mechanisms may provide insights into the brain harms attributed to cannabis use and/or the potential benefits of cannabinoid agonists or antagonists. Potential health benefits from cannabis and cannabinoids include treatment of childhood epilepsy and pain relief.5 Some of the harms from acute intoxication as well as chronic use include impaired driving and learning capacity, poor educational and other social outcomes, amotivation, adverse fetal outcomes, and other potential health effects.5

In recent years, the potency of cannabis (ie, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol content) has increased 3-fold to 4-fold,5 and the ways in which users consume cannabis have also changed, raising questions as to how these factors may or may not increase the potential for harm. Concurrently, the legal landscape regarding cannabis, including both medical and recreational legalization, has evolved rapidly. In this context, a key question has been whether the legal changes are influencing the rates of use. To address this issue, Hasin et al4 compared changes for states with and without medical marijuana legalization across 3 surveys conducted in 1991-1992, 2001-2002, and 2012-2013. They found a main effect of medical marijuana laws being associated with differential increases in cannabis use in states passing those laws. Furthermore, analysis of the 2 intervening periods between studies allowed them to differentiate between the early-adopting and the later-adopting states, which showed significant period and location effects. That is, there were significant variations within the broad cluster of states that have legalized medical marijuana.

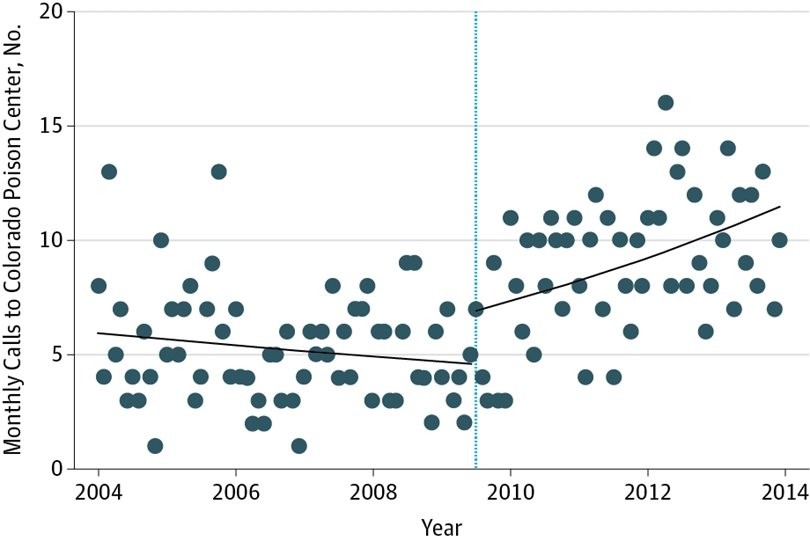

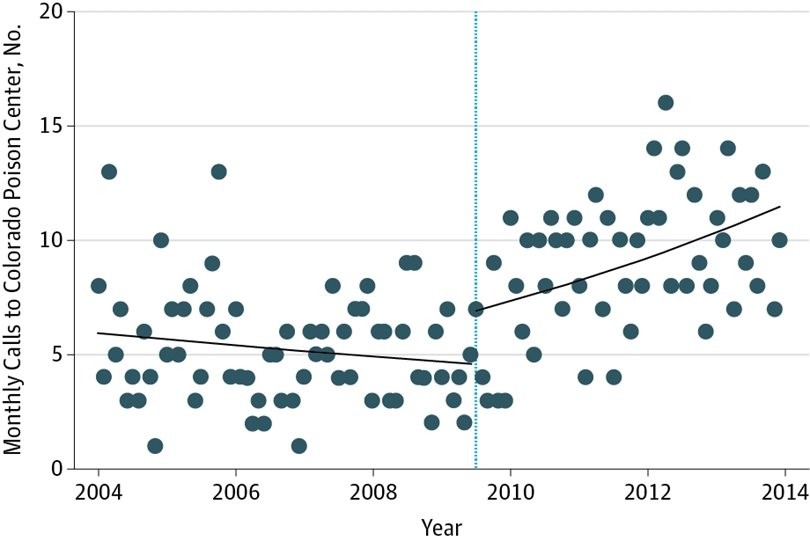

The data used for this study included assessment at only 3 points, which limits the ability to capture details about trends because the timing of the waves was not selected to reflect evolution of policies. For example, as noted by the authors, there was a significant marijuana policy modification in Colorado in 2009 that resulted in an explosion in dispensaries and medical user applications. Other research has documented a parallel increase in poison center calls, which illustrates how a single policy shift can have an effect on public health (Figure).7

Monthly calls to the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center regarding cannabis intoxication over time. The dots indicate the number of calls per month; the solid line, the best-fit trend line; the dotted line, July 2009, when the policy change was passed that allowed medical marijuana dispensaries. Adapted with permission from Davis et al.7

A significant issue is the diversity among marijuana laws and their implementation across states. Hasin et al4 analyze the effect of these variations and identify particular increases in marijuana use among adults in Colorado. However, because of data limitations other than for Colorado and California, they were unable to fully explore the ways that each state passing medical marijuana laws may vary in its specific trajectory of cannabis use. Thus, recognized variation in how states implement laws regarding marijuana8,9 could benefit from further explication with other data. For example, there may be greater migration of marijuana smokers into states that have such laws. Additionally, within a state’s marijuana laws, a specific component can have a negative effect9 but another component may have potential for benefit. For instance, Powell et al9 found a relative decrease in opioid deaths and treatment admissions associated with state dispensary laws, although not with medical marijuana laws more broadly. Examining the differential effect of the varied approaches to implementing medical and recreational marijuana legalization constitutes a valuable opportunity for marijuana policy research.2– 5,7– 9 Similarly, further research is needed to investigate how marijuana is consumed by those who use it for medical reasons, including doses, frequency, routes of administration, and concurrent use of other substances, including alcohol.5,10

Understanding the nuances of the laws to determine which components of a policy are associated with positive and negative effects and to balance potential harms and benefits should be necessary considerations for policymakers and those implementing state laws. While research continues to gather evidence to that end, clinicians are faced with the reality reinforced by the findings from Hasin et al4 that cannabis use is increasing among adults living in states that have legalized medical marijuana. In the meantime, it is clear that a robust system of education, prevention, and treatment is needed to minimize the negative consequences that might arise if cannabis use continues to increase.

Corresponding Author: Wilson M. Compton, MD, MPE, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, 6001 Executive Blvd, MSC 9589, Bethesda, MD 20892-9589 (wcompton@nida.nih.gov).

Published Online: April 26, 2017. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0723

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Compton reports ownership of stock in General Electric Co, 3M Co, and Pfizer unrelated to the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.